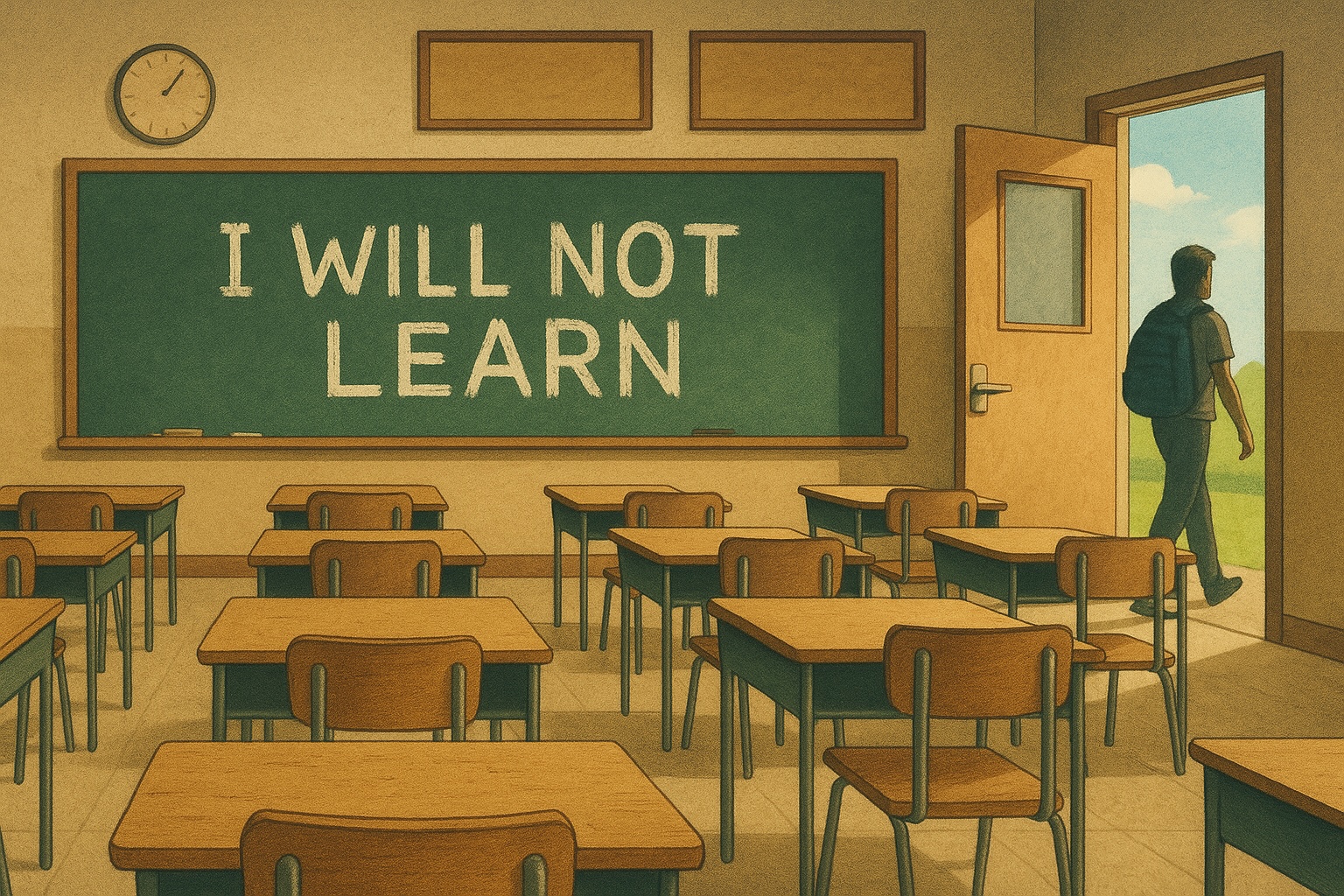

A candid discussion among educators online has brought a critical issue to the forefront: a growing apathy among students that feels fundamentally different this time around. Teachers report students who are not just bored, but are significantly “checked out,” viewing the traditional educational pathway as an obsolete relic. This isn’t a simple case of teenage disinterest. It’s a rational response to a world where the long-held promise, that a good education guarantees a stable, prosperous future, appears to be fracturing before their eyes. When a straight-A student genuinely asks, “Is college worth it?”, we must listen. This is not a failure of our students; it is a profound challenge to the very structure and purpose of our educational system.

The Broken Feedback Loop: When Effort No Longer Equals Reward

From a pedagogical standpoint, student motivation hinges on a reliable feedback loop. For decades, that loop was clear: work hard in school, get good grades, go to college, and secure a well-paying career. This extrinsic motivator was the bedrock of our system. Today’s students, however, are witnessing a system glitch. They see older siblings and family members, armed with expensive degrees from prestigious universities, working service jobs to chip away at mountains of student debt.

The anecdotes shared by teachers of UCSD graduates waiting tables and parents regretting their student loans, are not isolated incidents; they are data points. In learning theory, when a promised reward fails to materialize, the motivation to perform the associated task extinguishes. The student apathy we’re observing is a direct result of this broken feedback loop. They are logically questioning the return on investment for a system whose outcomes have become unpredictable and, for many, financially crippling.

An Unexpected Innovation: The Shift to Work-Integrated Learning

Amidst this challenging landscape, a fascinating and potentially transformative experiment is unfolding. A high school principal, in a move that some might see as devaluing education, has begun offering academic credit for students who hold down a job. This “work study” program allows them to gain real-world experience, contribute to their families’ finances, and engage with their community, all while fulfilling graduation requirements.

Far from being a step backward, this should be recognized as a powerful example of curriculum innovation in action. This is work-integrated, experiential learning, a concept long championed in higher education and vocational training.It implicitly teaches vital skills, professionalism, time management, financial literacy, that are often missing from traditional academic subjects. This principal hasn’t abandoned education; they have expanded its definition to meet students where they are, acknowledging that for many, the most urgent classroom is the world of work itself.

Designing the Future: Towards a More Agile and Relevant Education

The solution is not to force students into a binary choice between a traditional degree and a low-wage job. The challenge is to redesign the educational blueprint to be more agile, personalized, and responsive. The work-study program is a brilliant, localized adaptation, but we must think more systemically. How can we braid together academic learning and practical application from the very beginning?

This is where modern instructional design and educational technology can lead the way. We should be building systems that feature stackable credentials, where students can earn micro-certifications for specific, in-demand skills that can be applied immediately in the workforce and also count toward a future degree. Imagine high school curricula integrated with apprenticeships, project-based learning modules co-designed with local industries, and digital portfolios that showcase tangible skills, not just transcripts. We must move beyond the one-size-fits-all model and create a more porous membrane between the classroom and the economy.

The rising tide of student apathy is not a discipline problem; it’s a design problem. It’s a clear signal that our educational model, built for a different economic era, is no longer serving all students effectively. Instead of viewing their disengagement as a deficit, we must see it as a crucial piece of feedback compelling us to innovate. The goal is not to diminish the value of deep knowledge and critical thinking, but to situate it within a framework that also provides clear, accessible pathways to economic stability and meaningful work. The question for all of us, educators, administrators, and policy, makersis no longer *if* we should change, but how quickly we can co-design the future. What does a school that truly prepares students for the complexities of the 21st-century economy look like to you?